The idea of load balancing and proxies has been around for a while. In fact, the technology dates back to the 1990s, when hardware-based devices distributed the network traffic to back-end servers. As the world of technology evolved, however, so did the load balancer and the proxy, migrating eventually to software-based platforms.

Software-based load balancers, such as Kubernetes Ingress and NGINX, are now ubiquitous. Beyond that, however, there exists a whole new world of microservices and distributed architectures that bring unique and interesting challenges.

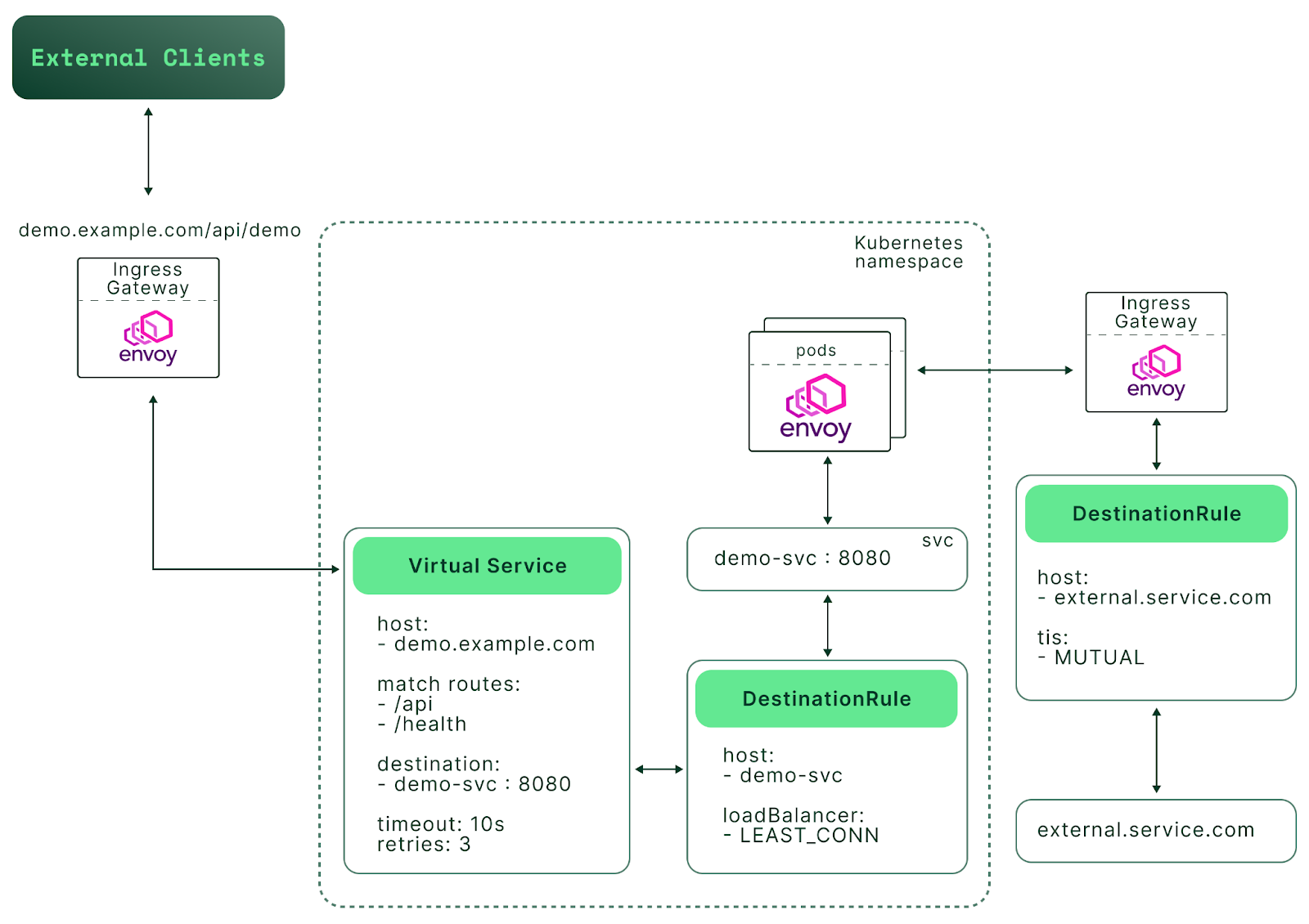

New players like Envoy and Istio have emerged to address many of these challenges, providing new ways to manipulate and secure traffic patterns.

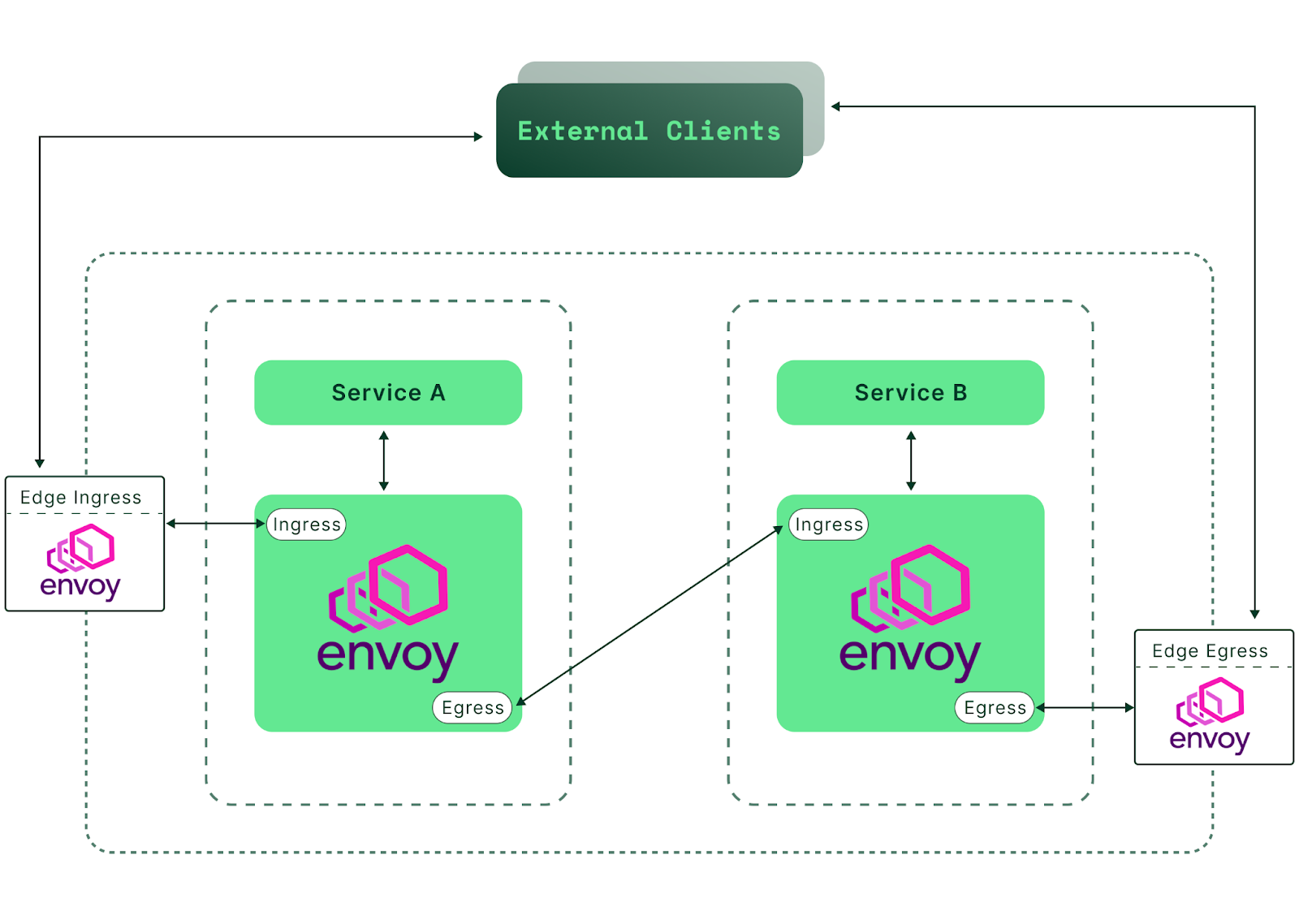

Let’s start with Envoy. What is it, and how does it fit into today's architecture? To quote their official site, “Envoy is an L7 proxy and communication bus designed for large modern service-oriented architectures.” It can also act as an L3/L4 proxy, an advanced load balancer, an edge proxy, and much more—as we will soon see.

Envoy was created in 2016 by Lyft and has had 72 major releases since then. It’s open-source, a CNCF graduate, popular, capable, and very well-maintained.

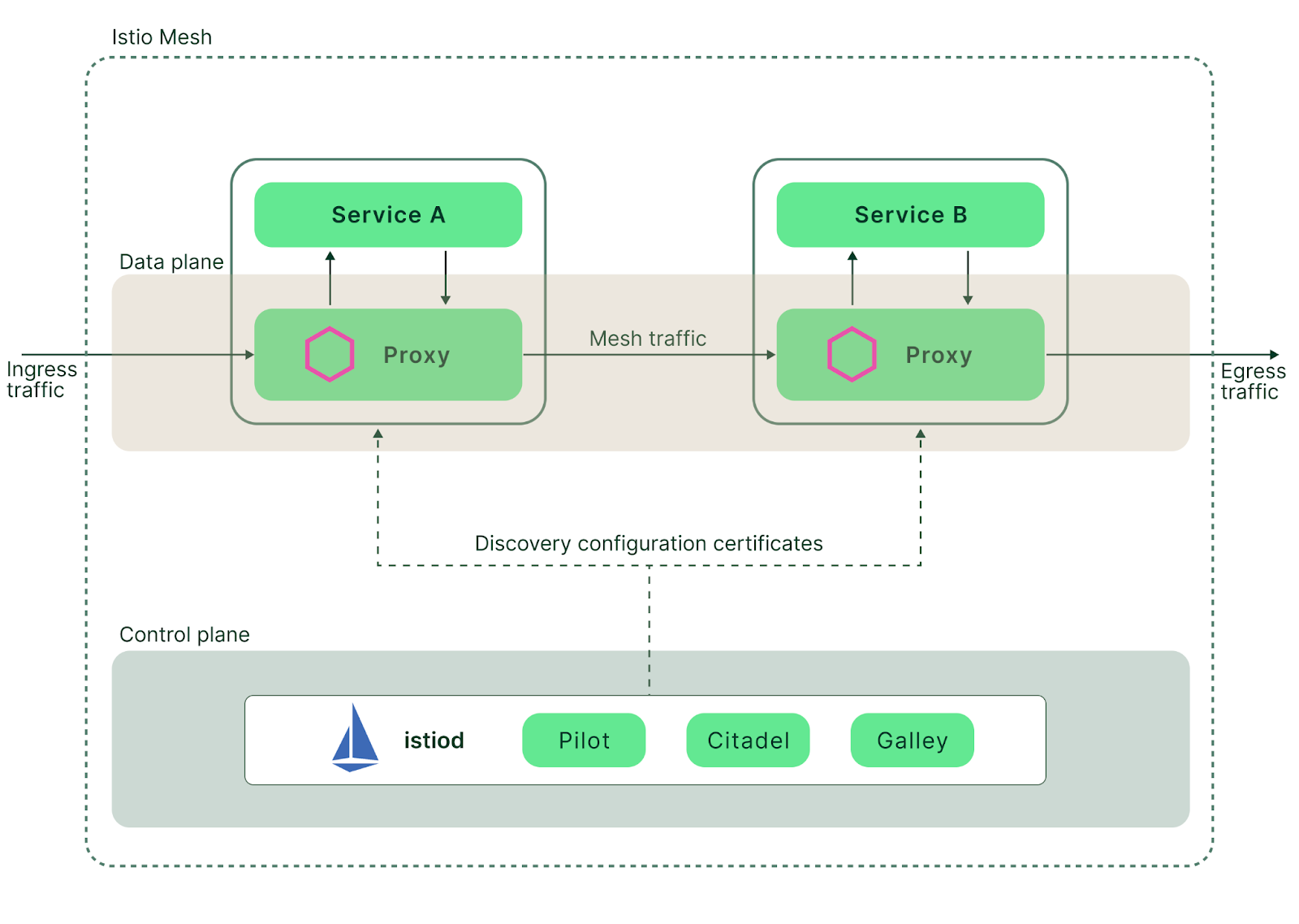

Next, we’ll introduce Istio. Istio was created in 2017 as a collaboration between IBM, Google, and Lyft. It Implements a whole new approach to communication between distributed applications. Istio is an example of what’s known as a “service mesh.'—that is to say, a dedicated infrastructure layer that runs alongside applications, interconnecting them. Service meshes give us greater control of network communications because they provide observability, traceability, and security. Furthermore, they do so without requiring that these communication-enhancing features are explicitly built into the applications themselves..In this article, we’ll look at Envoy as a core building block for Istio service mesh. Along the way, we’ll assess the features it brings to Istio, and highlight some drawbacks.